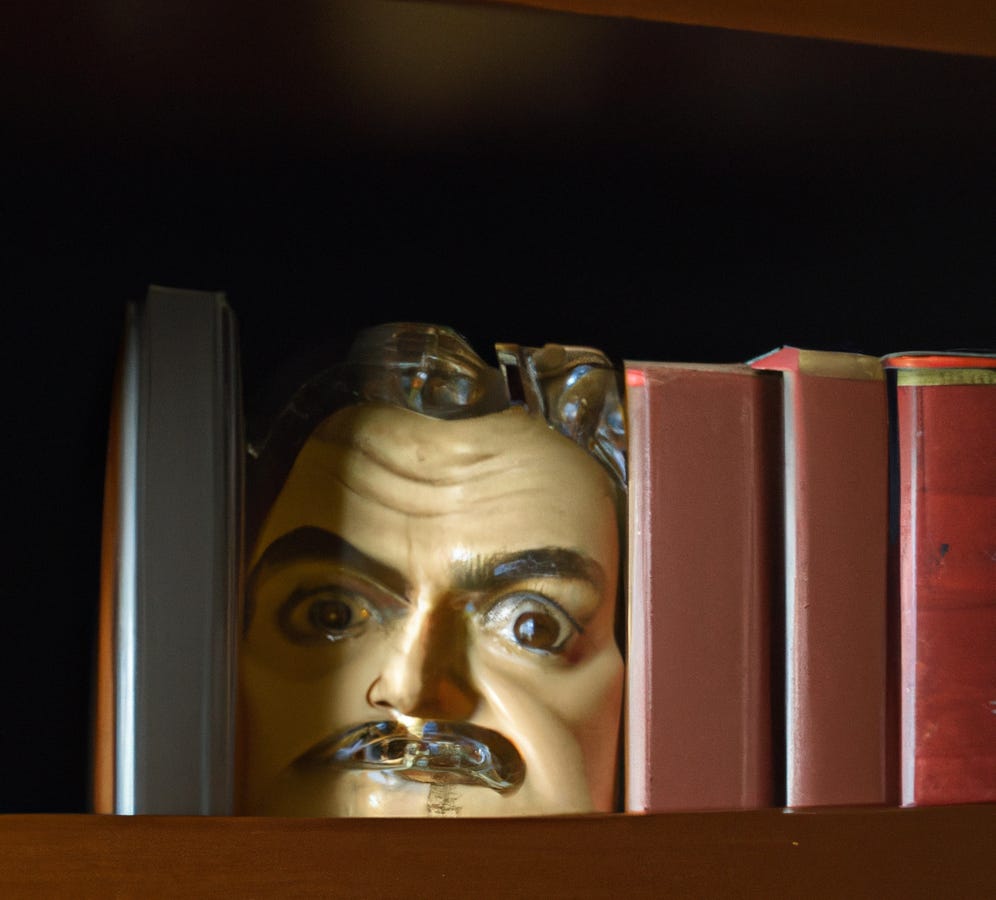

Just be your shelf.

How your experience of aesthetic pleasure is bound to your sense of personal identity

At koodos labs, we’ve been exploring interfaces to utilize and manage your personal data. We’ve been interested in helping people connect more deeply with themselves and with the people and media that inspire them. With that, we’re very interested in why we like what we like.

With that context in mind, I’ve been curious about how we form our tastes and what makes us like what we like. My thoughts here are heavily inspired by a number of perspectives on the topic, including the work of Matthew Salganik, John Deighton (one of koodos labs’ advisors), Susan Rogers, Ogi Ogas, Luke Burgis, W. David Marx, and many others.

In today’s piece, I share some of my takeaways from Susan Rogers and Ogi Ogas’ fantastic book, This Is What It Sounds Like — for more, check out their book here.

Before we jump in, a few announcements:

Will you be at SXSW? We're hosting an event with Crush Ventures. It'll be after-hours at a coffee roastery with a vinyl DJ, tacos and ~some announcements~.

The culmination of months of research — I published a high-level framework on progressive decentralization for fellow builders alongside my collaborator, Prof Scott Kominers.

We coordinated a limited working group on scaling cooperative platform models. The discussions led to a paper that has been in the Top Ten Download list on SSRN for multiple journals since it’s publication.

I identify as…

Our taste profile is formed through biology, experience and happenstance. Your random neural wiring, your exposure to media and culture in the time and place you grew up, and the sheer chance of consuming this piece and not that piece at crucial moments in your life all shaped your taste and influenced the kind of art, music, food, fashion, etc. that you can fall in love with. Your one-of-a-kind taste profile develops and evolves as your internal perceiving, thinking, feeling and social networks learn through experience.

If we were to disregard our broader need for societal acceptance and status — we’ll return to these in a future piece — then our true taste profile at any point in time isn’t something that we choose any more than we choose our height or sexual orientation. The art that tickles our mind isn’t something that we can control. All we can do is be open to learning what this wandering can teach us about our true nature — whether we’re musically attracted to Billie Eilish or Billy Idol. In human relationships and musical relationships, our opportunities for fulfillment start with being honest with ourselves about what we are truly attracted to. In short, the way our mind reacts to art is less something we cultivate, and more something we recognize.

Because each of our brains are wired to experience rewards from different facets of music, we’d be misguided to think that anyone’s taste is superior to anyone else’s.

The neuroscience of liking a song

Our most private dreams and fantasies — the fears, hopes, and longings nestled deep in our psychic core — are all bound together in a neural network in the brain, one associated with our sense of self. One of the best ways to activate the personalized “self network” is by consuming art that resonates with the sweet spots on our taste profile. For example, when we’re immersed in the enjoyment of a favorite record, our mind-wandering network lights up like fireworks.

The music you respond to most powerfully can reveal those parts of yourself that are the most “you” — those places your mind unerringly returns to when it is daydreaming or fantasizing.

As our brain is idling, the contents of our reveries — what the psychologist William James labeled “flights of the mind” — contribute to the conscious conception of our personal self. Whenever we daydream or fantasize, our mind drifts to places that are intimate and private, thinking about what we like, what we need, and what we desire. Thus, when we listen to music we love — music that aligns with our sweet spot — we activate the part of our mind that fuels the deepest currents of our identity.

Beyond that, when we’re consuming something, we naturally start to link our personal experience to the experience of the art. Nobel Laureate Eric Kandel explored how when we view a painting, we start to evaluate whether the ideas and feelings it evokes within us match our self-concept. Our memory circuits kick into retrieval mode rather than encoding mode and we automatically “play back” memories of people, places, and events that we associate.

So what do we end up liking? Cultural artifacts that maximize the reward of letting our minds wander — rewards linked to our deepest conception of personal self. And this can be different at different points, for example sometimes we need to access our most-buried emotions, while other times we need to feel our inner dance, warrior or athlete. Sometimes we need words to express our tangled thoughts, other times we’d like to visualize an impossible romance. We turn to our favorite records, videos, poems to take us where we want to go — where we need to go.

Be it art or romantic partners, we fall in love with the ones who make us feel like our best and truest self.

Sharing AUX, sharing myself

Gaining insight into a friend’s musical tastes can be an intimate experience that reveals how they see themselves in relation to the world, the value of aesthetic experiences in their lives, or who they want to be when they grow up (or who they wanted to be). In many ways, when we play a song for a friend or send them a recommendation, we aren’t merely sharing the content with them, but we’re letting them in on a part of who we are. This doesn’t just apply to music, but extends to other cultural artifacts.

Interestingly, the identity constructive aspect of culture tends to be more pronounced in our more formative adolescent years. That’s because, neurally, what teens think of themselves is almost identical to their impression of what others think about them. Effective social cognition relies on self-knowledge and self-awareness, and both are under development through adolescence. This is also why lots of social apps, which tend help us temper our view of ourselves, start with a young audience — beyond that group just having more time on their hands.

Beyond a personal resonance, there’s a confluence of external factors for why we like what we like — and also what we say we like. We’ll explore those in a future article.